In vier blogs had

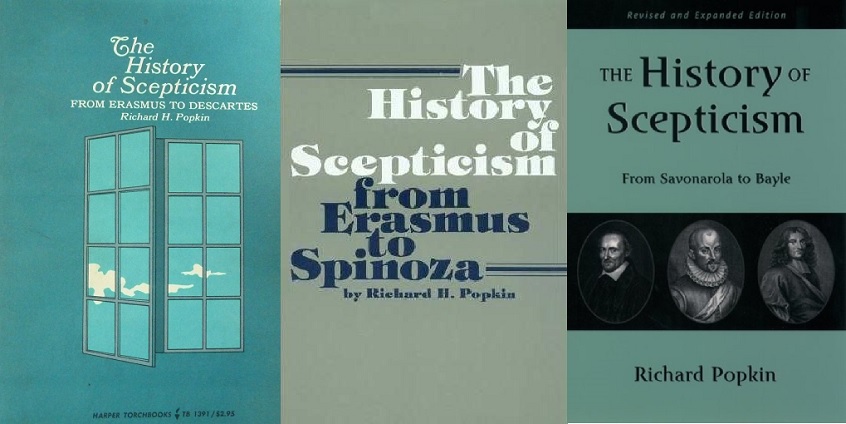

ik aandacht voor Richard Popkin’s Spinozastudie: op 12 juli

2009 het blog: “Richard H. Popkin

(1923 - 2005) - zijn Spinoza-boekje”; en in het blog van 31 okt 2011: “Spinoza scepticus?” O.a. over het boek

van Richard H. Popkin, The History of Scepticism from Erasmus to Spinoza. Op 23 januari 2019 tenslotte meldde ik dat

Richard Popkin’s The History of Scepticism met Chapter 15 “Spinoza’s Scepticism

and Antiscepticism” op internet staat.

|

| 1960 1979 2003 |

Twee blogs

had ik [nl. op 6 en 9 febr. 2012] met de vraag “Waarom ontving Richard Popkin

niet de Nobelprijs voor Spinoza Studies?” Dit n.a.v. zijn “Serendipity at the

Clark: Spinoza and the Prince of Condé,” [Clark Newsletter 10 (1986), pp. 4–7.],

dat ik in dat tweede blog overnam.

“Popkin’s

Spinoza”

Sarah Hutton schreef een gedegen en informatief overzichtsartikel over hem, “Popkin’s Spinoza”: het derde hoofdstuk in Jeremy D. Popkin (ed.), The Legacies of Richard Popkin (2008).1) Dat hoofdstuk was – mét kleursignaleringen van een uploader – als PDF hier te vinden [toevoeging 5-9-2019: daar het stuk daar alweer is verdwenen, heb ik het naar hier geüpload]. Ze benadrukt dat zijn bredere historische studie "enabled him to contribute immensely to the reconstruction of Spinoza’s intellectual milieu, peopling it with figures previously ignored, or unknown, such as Menasseh ben Israel, Orobio da Castro, Uriel da Costa, Isaac La Peyrère, Jacques Basnage, Henry Oldenburg, Margaret Fell, Samuel Fisher, Adam Boreel and Henry Morelli."

Het is vanwege de notitie van Sarah Hutton, “Popkin follows this [Bayle's] detective model of investigation” [p. 36], dat ik de kop van dit blog formuleerde. Op meer plaatsen trouwens verwees ze naar hem en zijn aanpak als naar [die van] een detective. Die indruk wordt duidelijk bevestigd door hoe hij zelf over zijn onderzoek naar Spinoza schreef - een tekst die ik hierna overneem.

Sarah Hutton schreef een gedegen en informatief overzichtsartikel over hem, “Popkin’s Spinoza”: het derde hoofdstuk in Jeremy D. Popkin (ed.), The Legacies of Richard Popkin (2008).1) Dat hoofdstuk was – mét kleursignaleringen van een uploader – als PDF hier te vinden [toevoeging 5-9-2019: daar het stuk daar alweer is verdwenen, heb ik het naar hier geüpload]. Ze benadrukt dat zijn bredere historische studie "enabled him to contribute immensely to the reconstruction of Spinoza’s intellectual milieu, peopling it with figures previously ignored, or unknown, such as Menasseh ben Israel, Orobio da Castro, Uriel da Costa, Isaac La Peyrère, Jacques Basnage, Henry Oldenburg, Margaret Fell, Samuel Fisher, Adam Boreel and Henry Morelli."

Het is vanwege de notitie van Sarah Hutton, “Popkin follows this [Bayle's] detective model of investigation” [p. 36], dat ik de kop van dit blog formuleerde. Op meer plaatsen trouwens verwees ze naar hem en zijn aanpak als naar [die van] een detective. Die indruk wordt duidelijk bevestigd door hoe hij zelf over zijn onderzoek naar Spinoza schreef - een tekst die ik hierna overneem.

Eerst neem

ik hier de obutuary over die Sarah Hutton over Richard Popkin schreef in The

Guardian (7th May, 2005 – tekst hier

te vinden.)

In the

field of the history of philosophy, Richard Popkin, who has died aged 81, was

best known for his work on scepticism, and especially for his classic study The History Of Scepticism From Erasmus To

Descartes (1960).

A professor

at the University of California, San Diego, (1963-73) and Washington

University, St Louis, Missouri (1973-86), he was among the founders of the Journal Of The History Of Philosophy,

and, with Paul Dibon, started the International

Archives In The History Of Ideas; he also wrote about the 1963

assassination of the US president, John Kennedy.

The History Of Scepticism

revolutionised the received picture of both the history of philosophy and the

history of science, by demonstrating the influence, in the century before

Descartes, of ancient Greek sceptical arguments about the impossibility of

knowing God and the world.

In making

his case for this central contribution to the development of modern science and

philosophy, Popkin gave attention to the intellectual context of the time,

especially the role of religious disputes in the take-up of philosophical

scepticism deriving from the discipline's Greek founder, Pyhrro. Instead of

treating the history of science and philosophy as a series of breakthroughs by

canonical figures, Popkin sought to view the thought of the past from within

its own framework...

Popkin also

achieved fame with The Second Oswald

(1966), the book in which he disputed the findings of the Warren commission

that Kennedy was killed by a lone assassin. He foresaw the rise of religious

fundamentalism in the United States and the Middle East, contributing an

analysis of its American dimension in

Messianic Revolution (1998, co-authored with David Katz). He also wrote for

a general philosophical readership, with such books as Philosophy Made Simple (co-authored with Avrum Stroll, 1969).

Popkin was

an inspirational teacher who gave great encouragement to younger scholars, such

as myself. When I first met him, I was struck by his wry sense of humour, and

the touch of scepticism that ensured he never took himself or others

over-seriously. All who knew him remember his generosity; and he was always

good company and an entertaining raconteur.

Hierin

werd zijn Spinoza-studie nog niet genoemd maar dat ‘maakte ze dus ruimschoots

goed’ met haar “Popkin’s Spinoza.”